Sky Computing

A talk on Sky Computing

Welcome to my talk on “Sky computing”, or “How am I going to get my app on the internet in the next ten years, maybe”

I’ve presented this at a couple of events, most recently at London Ruby User Group.

Slide 1 - About me

Slide 1 - About me

I’ve been a developer for over 20 years, and am the lead developer at a digital services consultancy called Unboxed. For most of our projects we use Ruby on Rails - some of you may be familiar with our CTO Andrew White, and his contributions to the rails project.

My background generally is: apps on websites, so started off at startups - not billions of requests, high concurrency, globally geo-located server farms - and 20 years ago, quite modest websites and apps, maybe 100 concurrent users. We support a range of apps that range from this size, to much larger scale apps, but when talk about my perspective of “putting an app on the internet” I’m being quite subjective with my experience - your milage may vary.

Slide 2 - Mainframe computing

Slide 2 - Mainframe computing

Mainframe computing was how organisations did big computing jobs from the 60s on. It was, in essence, computing as a utility. You could pay as you go. They were big proper computers, that took up rooms and rooms of space, with beeps and lights and people who wore suits to the office. Organisations would rent out mainframes by the hour to do things like payroll and big bulk data processing.

They were the precursor of concepts we know in cloud computing now - time sharing, batch processing… and we also would pay for things like backup and redundancy, that would be part of the service offered. Mainframe computers were used up until the mid nineties, and by then, of course, microcomputers and the IBM PC were common in the office, letting the average office worker be fitter, happier, more productive with their office PCs.

Slide 3 - The server room

Slide 3 - The server room

The server room. A room inside your office building. You own it - It’s all yours. Security, complete control, access, maintenance, climate control, networking, backups, connectivity - you also own that.

When I started as a software engineer, I worked at academic institutions and medium sized enterprises, and how we’d get an app served on the internet, or intranets, was in the server room. I was working at a large marine biology institution on an app that would record scientific data, and to update the app, we would go into the server room, power down the sun microsystems server, wheel it out, take it the office, perform the update via CVS, and put it back in the server room.

Now that was complete control over your infrastructure, complete physical, literal control. You owned the equipment, you looked after the equipment, the temperature, the software stack, the power, the fire systems, the off site tape backups, and so on.

Slide 4 - Dedicated servers

Slide 4 - Dedicated servers

Organisations were outsourcing all of that palaver 🇬🇧 Rent from Rackspace, or Fasthosts, or many other small hosting firms “Managed” or “Unmanaged” You got to know your support person very well Virtualisation was coming

Dedicated servers became more popular in the 2000s for hosting websites, running business applications, and other workloads that required dedicated resources and reliability.

Running them, and all that entailed, was outsourced to these hosting providers. It’s quite hard to research who were the big players at the time, but in the UK I remember Rackspace and Fasthosts, and a whole heap of other small hosting firms.

You still had absolute control over hardware and resources, its just you didn’t own them anymore.

They now existed in a temperature controlled cowshed somewhere on the M5 corridor. You’d have ‘managed’ or ‘unmanaged’ levels of support, and either way you got to know your support person very well. Splitting up these single machines was starting to happen, where CPU and disc space would be sliced up, and offered as virtual machines.

Slide 5 - Buckets

Slide 5 - Buckets

AWS, Amazon Web Services, was started in 2006. It’s first big consumer offering was ‘Buckets’, or S3, Simple Storage Service, in 2007. The problem of how to store files and all that entailed for most developers was largely solved. It was also a Content Delivery Network, which was available for a very cheap rate, and this was the first of it’s big services.

Very quickly it became a default. When faced with the problem of file storage, this was the solution. How-To’s for developers were written, and S3 was the go-to for this problem. Wordpress plugins were written and developers started just learning about S3 when it came to storage. It was on its way to becoming a monopoly, not just in terms of market share, but in development mindsets.

Slide 6 - Utility Computing

Slide 6 - Utility Computing

“the long dreamed vision of computing as a utility is finally emerging.”

In 2008 AWS released EC2, or elastic cloud compute. This, again was computing where ‘you pay for what you use’. Elastic compute services allow you to choose from a variety of instance types or virtual machine configurations to match your specific requirements. The step up from the virtualised server offerings was that resources felt unlimited - you could scale up and down very quickly, without having to speak to your support person. They offered co-location, geographical redundancy, and so on. A whole heap of other problems were starting to be solved for you.

In 2009, a group of academics from Berkeley uni released a paper that declared that “the long dreamed vision of computing as a utility is finally emerging.” This was true utility computing.

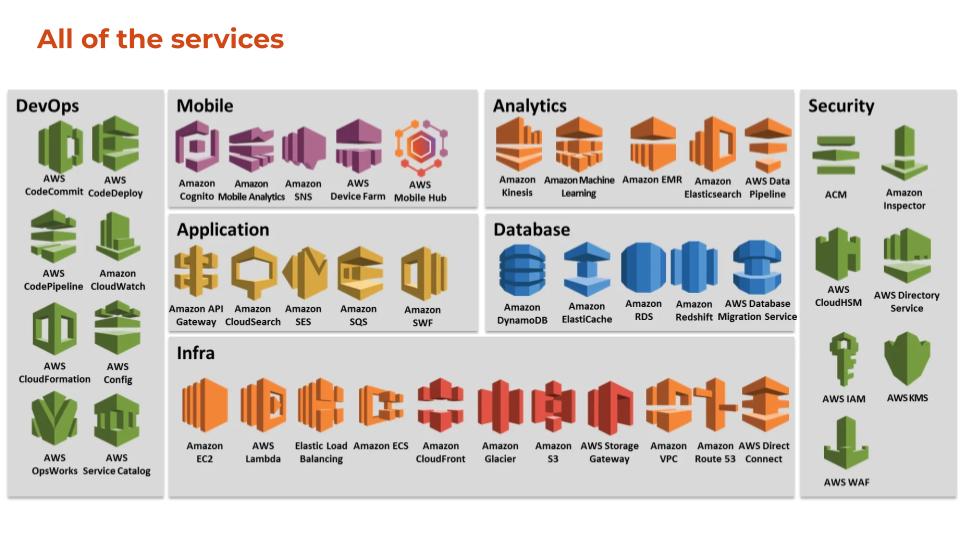

Slide 7 - All of the services

Slide 7 - All of the services

This is a slither of what AWS offers now in 2024. Us developers love them. Generally, each one of these will be running on some modified piece of open source software, or at least taken the foundations of OSS, and has been highly optimised by very talented engineers to handle the huge demands and requirements of running on Amazon infrastructure. It takes away huge amounts of time and effort, and lets us focus on delivery the goods.

Where I work at Unboxed, we use a combination of these servers to easily manage spikes in traffic with ease, often highly automated processes, that make life easier with way less resources. We run the UK government petitions website, and when a contentious petition gets posted, it’s a breeze to handle the increase in requests and server load. We’ve had petitions with 4 million signatories, and they’ll often come at awkward times like 4pm on Christmas Eve.

When a new project comes along, whilst of course we can host it on Azure, AWS or GCP, we often think of AWS services that would solve problems because that’s been some of our developers ecosystems for their entire professional career, and the rest of us for at least a decade.

Choosing a provider currently is a case of ‘which billionaire should we give our money to’. It’ll be one of the big 3 - Google, Microsoft, or most likely, Amazon. And when you choose your host, you are locked in.

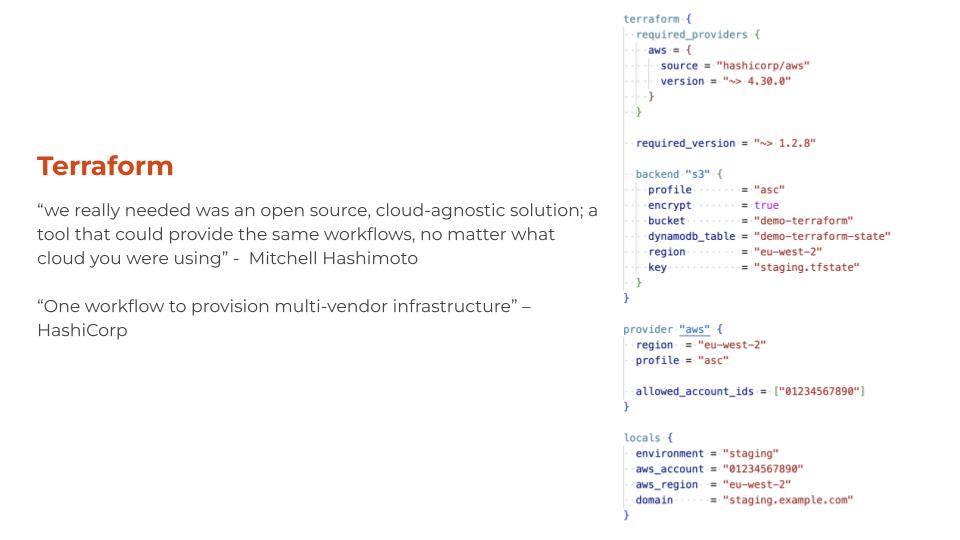

Slide 8 - Terraform

Slide 8 - Terraform

“One workflow to provision multi-vendor infrastructure” – HashiCorp

An example of how locked in we are can be seen in Terraform configs. Terraform is a infrastructure-as-code tool. It is a step towards being cloud agnostic - single configurations can manage multiple providers and handle cross-cloud dependencies. It’s not designed to be totally agnostic - you still have to declare different backends for the cloud provider you are using.

The differences in the cloud providers mean that cloud agnosticism isn’t going to happen. For each of the big 6 cloud service providers - I’m including salesforce, IBM and oracle’s cloud offerings - security is handled very differently. Different concepts and analogies are used to describe how data should be securely transmitted, and who has access. For most projects, it would be a significant overhead to merge from one provider to another. You can see this in a typical terraform config - vendor specific language is used all the time.

Slide 9 - The vision

Slide 9 - The vision

So, what is sky computing? The same scholars, who released the influential paper in 2009 about cloud computing, released a paper in 2021 declaring that there isn’t one single underlying cloud platform with a set of open standards that anyone can use. Cloud computing has become a series of proprietary platforms. They have proposed a concept called ‘Sky Computing’ - a layer above cloud platforms that enables interoperability between clouds.

The vision of the paper goes back to the ideal - commoditized cloud computing. “To fulfil the vision of utility computing, applications should be able to run on any cloud provider (i.e., write-once, run-anywhere)”

The paper - quite a short paper, and readable at 6 pages - talks about the future of cloud computing, the problems with current cloud offerings, offer a ‘reciprocal peering’ solution, and a look at technical barriers.

Slide 10 - How would this work?

Slide 10 - How would this work?

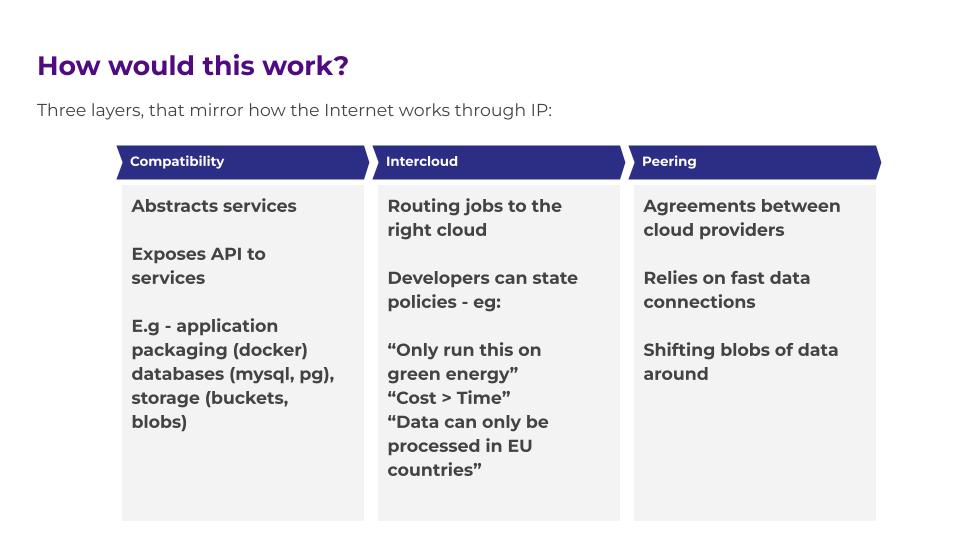

Three layers, that mirror how the Internet works through IP - compatibility, intercloud and peering.

The compatibility layer roughly translates to the current service offerings by todays cloud providers.

The intercloud layer is where you can negotiate with different providers - so you can say whether you want to minimize costs or time for example. From what I’ve read, this also allows for interesting ‘contracts’ to be given and agreed upon between developers and providers - for example you could state ‘The power for this computing must be provided by green energy providers’. We work with a lot of public sector organisations and private companies who are becoming increasingly interested in supply chains and sustainability - could we offer this guarantee of green energy to clients, and not be locked down to a single provider? It also offers interesting policies where you could state a job that doesn’t need to be done quickly could be put on lower priority cycles to save compute costs. And of course the GDPR classic, data in the EU only.

The peering layer is where cloud providers would have to speak to each other, and offer financial and technical agreements, but from what I can see is mainly around shifting the data between providers for processing.

Slide 11 - Where’s the benefit?

Slide 11 - Where’s the benefit?

I’ve been a little bit opinionated around benefits here - does it matter if developers purely have a vendor specific way of thinking, or that open source projects get black boxed and turned into mystery services? What would be the benefit to developers?

Well there is cost. The big man himself, DHH, wrote a blog post a year ago called “Why we’re leaving the cloud” - for Basecamp, which outlined frustrations around AWS in particular - with a profit margin of 30% - as well as talk about the resilience of the internet in general. If we’re all on the same big six hosts, thats not what DARPA designed ARPANET for - the internet was designed to have many different routes from A to B and back again - if we’re all on the same 3 or 6 hosts, this can be an issue. When AWS has outages, as rare as they are, it is noticeable to consumers on the internet

Large language model processing is a hugely costly business that is presently not available to many. Data is getting cheaper and quicker to shift around - If there were services that could offer the compute power for this sort of work at off-peak times, this would democratise and open up this tech. There is also newer innovation to be made by providers. Currently, if the national grid makes a load of excess energy at night that isn’t being used - could that be offered to hosting firms for a load of compute intensive jobs to be ran overnight? Finally the ability to lift and shift your app when a host has let you down adds more competition to the marketplace.

Slide 12 - What are the risks?

Slide 12 - What are the risks?

The compatibility layer in particular is the commoditization of cloud providers, which is not in the interests of incumbents. There’s a concept in capitalism of ‘Perfect Markets’. I’m not an economist but this occurs when the only inputs are supply and demand, which forces prices down. Incumbents don’t want this - they want to avoid this state - they like it when their margins are so high. The classic argument of a service based compatibility layer stifling innovation through a speciality service being offered that wouldn’t fit the standard. Lets say one of AWS’s more out there offerings - the one where you can hire a satellite for an hour. I’m not sure a sky computing proposal would actually prevent a nice service like this being offered, it would just be only possible through one provider.

The agreements between providers would essentially make data transfer free, so whether or not that is a realistic thing remains to be seen. The data would also have to be secure. Theres already big changes between how security is managed at different providers so this would be a challenge.

Monitoring - I put that in there as I could see monitoring applications - logs for example - would get very complex.

Creating a service directory - again this is standardization, and getting providers to agree to offerings. You can see what current services could be offered in a compatibility layer API - compute, storage, it’s just making those differences work.

So what next?

Slide 13 - Who is going to do this?

Slide 13 - Who is going to do this?

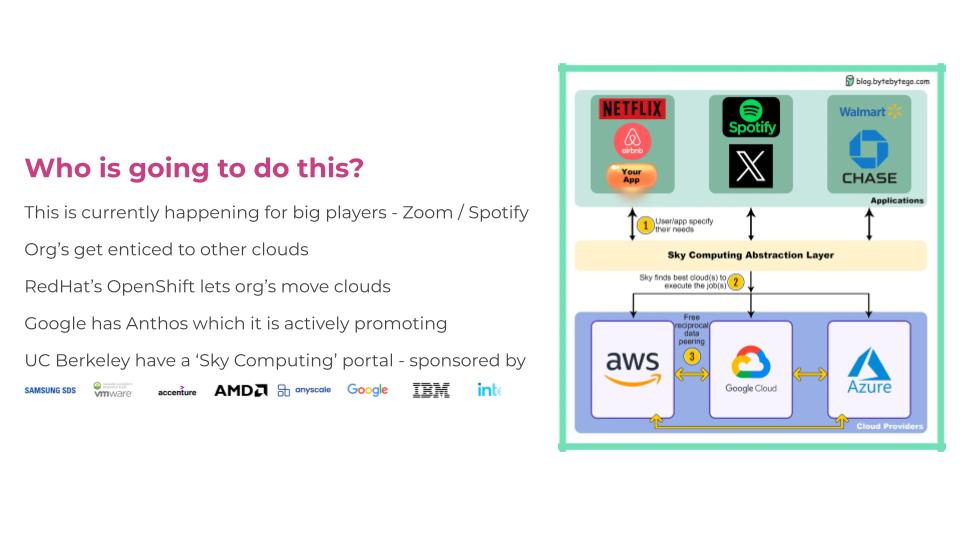

Big players have the ability to negotiate with cloud providers and have the ability to lift and shift between providers now. A couple of examples are Zoom and Spotify. Zoom obviously experienced some huge growth in 2020, and has chopped and used slices of cloud providers, starting off with Oracle, using a bit of Azure, and last reports suggest it’s currently best mates with AWS.

You would think the incumbents would not be interested in the ability to move providers easily, however AWS is dominant at 60%. Why wouldn’t the ‘smaller’ firms want to enable this? Researching this paper, you get a lot of paid placement style advertorials promoting multicloud or hybrid cloud approaches, and they’re all from Google cloud, oracle, IBM ‘contributors’ that want to promote this as a future.

Google has a product called Anthos, which is mentioned in the paper, which is akin to Kubenetes, and is supposedly possible to move providers using it. That works on GCP and AWS.

University of California have made a webpage with its own domain at sky.cs.berkeley.edu. There’s lots of corporate logos on there, so there are some heavy players involved. The 2009 paper ‘Above the Clouds: A Berkeley View of Cloud’ featured ‘Ion Stoica’ and ‘Scott Shenker’ went on to be prophetic, so this may well be the future of how you get your app on the internet.

Slide 14 - A prophetic redditor

Slide 14 - A prophetic redditor

I’ll leave you with this response from the discussion about Basecamp leaving the cloud.

Sources:

- “Sky Computing, the Next Era After Cloud Computing” - Richard MacManus, The New Stack

- “Above the clouds: A Berkeley View of Cloud Computing” - Armbrust, Fox, Griffith, Joseph, Katz, Konwinski, Lee, Patterson, Rabkin, Stoica, Zaharia

- “From cloud computing to sky computing” - Stoica, Shenker

- “Why we’re leaving the cloud” - David Heinermeier Hansson, HEY.com

- “The Myth of Cloud Agnosticism” - Brandon Evans, SANS.org

- “The Future Of Computing: Supercloud And Sky Computing” - Bernard Marr, Forbes

- “The Story of HashiCorp Terraform” - Mitchell Hashimoto, Hashicorp

- Sky Computing Lab - UC Berkeley